In “Shanghai Modern: Reflections on Urban Culture in China in the 1930s,” Leo Ou-fan Lee examines the many factors which contributed to the golden age of Shanghai urban culture. During the early twentieth century, Shanghai was the center of China’s new media culture, connected by the major nodes outlined in this chapter: architecture and urban space, department stores, coffeehouses, dance halls, and parks fueled the city’s newfound sense of cosmopolitanism.

I found it especially interesting to read Lee’s text after our discussion of modernism in Meiji Tokyo. As John Clark explains in “Doing world art history with modern and contemporary Asian art,” the term ‘modernism’ is often used to describe innovations in cultural and artistic production, but there is danger in applying ‘modernism’ as a blanket term in East Asia.

The readings thus far seem to support Clark’s claim that, even more so than African modernities or Latin American modernities, East Asian modernities remain bound to Euro-American influence. Christopher Bush, Associate Professor of Comparative Literature at Northwestern University and an expert in interactions between Euro-American and East Asian aesthetic theory, avant-gardes, and media, argues that much of the scholarship around East Asian modernisms has been reductive: “Nonetheless, many of the interpretive models offered by postcolonial criticism do not apply to East Asia, which was never colonialized by a Western power and indeed produced its own imperial power in Japan.”

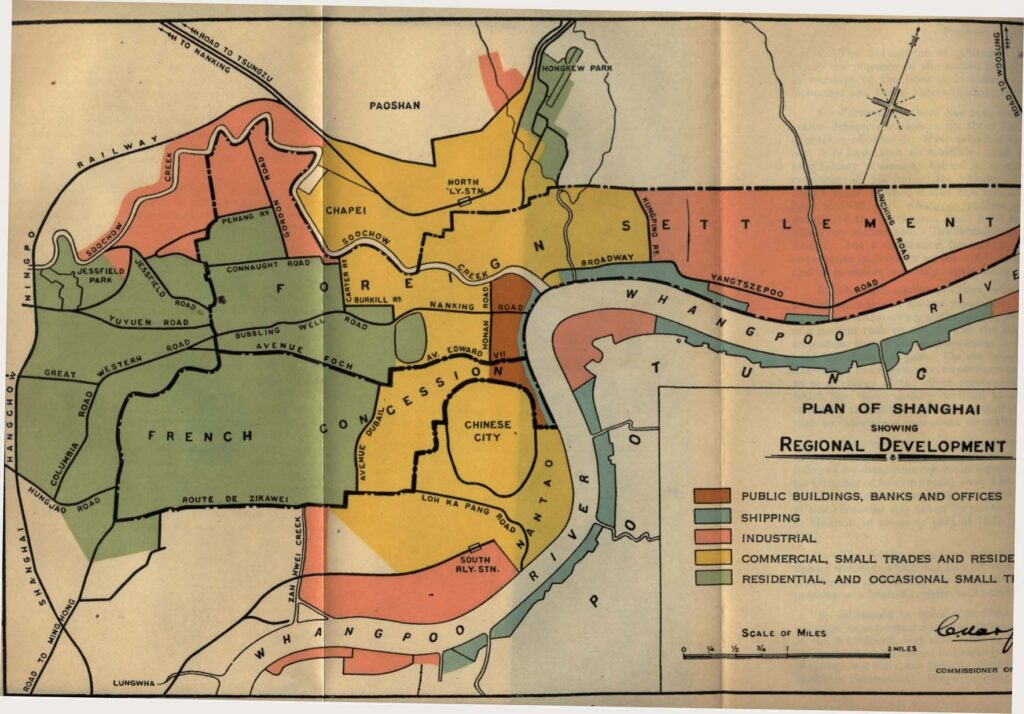

While we certainly saw the direct influence of Western ideas on Meiji Japan—a number of renowned European architects and scholars were expatriated to Japan with the goal of modernizing the nation—Shanghai presents an even more explicit case study because of its international concessions. These concessions show how Chinese modernism was shaped by profound geopolitical asymmetries with the West.

Both Bush and Lee agree that until recently, modernism has been a relatively overlooked category in Chinese literary history, viewed as an imported phenomenon limited mostly to Shanghai and out of step with the main current of modern Chinese literature. More recently, there has been renewed interest in modernist Shanghai, “the fifth largest city in the world by 1930 and an international crossroads with more than 300 bookstores, a thriving film culture, and, in the foreign concessions in particular, the latest technological innovations. Shanghai modernism had both parallels to and direct connections with those of Europe and Japan: the prominence of cinema and a new mass culture, the new woman, the disorienting tempo of metropolitan life and its reordering of experience.”

This is all to say, I find Lee’s characterization of Shanghai as “at once intrinsically Chinese and profoundly anomalous” interesting, and it made me consider how similar “cultural anomalies” might exist across the globe.

Sources:

Bush, Christopher. “Modernism in East Asia.” The Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism. : Taylor and Francis, 2016.

Lee, Leo Ou-fan. “Shanghai Modern: Reflections on Urban Culture in China in the 1930s.” Public Culture 1 January 1999; 11 (1): 75–107.